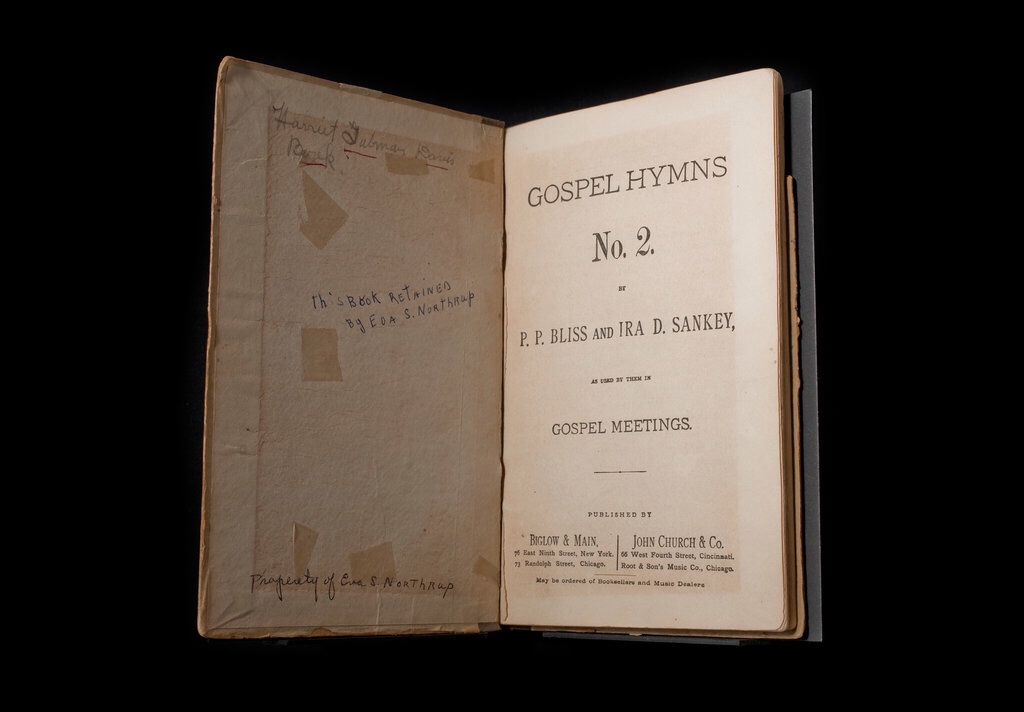

We don’t borrow

from Africa,

we utilize

that which was ours

2 start with.

The culture

provides a basis

4 revolution

+ recovery. / -Maulana Karenga

(7 Days of Kwanzaa. 7 Excerpts from Chapter 3 of a forthcoming essay series, #CELEBRATE: Meditations on a Black Festive Culture)

Kwanzaa has a second giant to face: in the late 1970s period, the holidays had to resist against the increasing capitalism of America’s cultural institutions (i.e. museums, media, etc.). Specifically Kwanzaa had to take heed to the mainstreaming of multiculturalism. Still, we have to understand that Kwanzaa’s commercialization was complicated. Differing views on promotion and profit, exploitation and appropriation, and markets and multiculturalism caused much debate amongst Black Nationalists adopters as is true today.

Some saw Kwanzaa as a vehicle for black participation in mainstream economic markets. They felt this was further continuation of the black cultural revolution. Others opinions wanted to invite white corporations to take part in the promotional campaigns for Kwanzaa. And then the most separatist opinions argued for a Kwanzaa was and should always be anti-commercialization. They argued that any type of commodification undermined the holiday’s reverence and sanctity.

By the late twentieth century, the high visibility was almost entirely due to the appropriation of corporate, cultural and media institutions to gain black market share. But, in turn, the commercialization served to legitimize Kwanzaa in American public culture. Though the drive for the continued observance of Kwanzaa was shaped by Afrocentric perspectives in the 80s and the revival of Black Power styles in 90s, the political vocabulary from the 60s and 70s had became diluted into the cultural philosophy of multiculturalism.

See, in the 1980s and 1990s, the importance of ethnicity and diversity provided previously unrealized access for people of color in a way that made them more politically, culturally and economically viable. But, it also made ethnicity a hot commodity for white owned corporations. While it’s true that entrepreneurs of color had more opportunity in this period, large white retailers primarily dominated the market for Kwanzaa promotion and black holiday observance.

So what is Kwanzaa’s fate today? Basically, racial holiday markets provide companies a chance to increase profits while engaging in the peddling of diversity, inclusion and recognition. Black History Month has held this promise for some years now. But, museums and other cultural institutions aren’t exempt. Public discourse has folded Kwanzaa a standard part of an American year-end holiday trio. This does little more that present Kwanzaa as a token nod to diversity. And the celebration is often acknowledged simply out of goodwill or lip service for predominantly white serving institutions. Kwanzaa’s celebration in the public sphere was inherently tied to the marketplace and not a broadening of the American cultural landscape such as St. Patrick’s Day.

Keith Mayes summarizes, “with the death of Jim Crow, Black political liberation opened up American society. Freedom, however, is a two-way street. If African-Americans gained access without, that means the dominant society also obtained liberty to move in.”

Much like black lives, Black cultural celebrations only matter when they make American dollars.

But, we know better.

So we celebrate. 🎉

keep celebrating. Ashé.

(6/7)

Read more on Kwanzaa’s 50th anniversary from its founder, Prof. Karenga here: http://www.ebony.com/wellness-empowerment/kwanzaa-50th-anniversary-karenga#axzz52vDztAJl

thank you for going on this journey with me. Much gratitude to @HouseOfMamiWata in Houston, TX.

Works cited to follow.

Look out for the full mediation – #CELEBRATE: Meditations on a Black Festive Culture.

As always,

peace & blessings

to you,

family.

Keep celebrating,

-S.